Unlocking our Transport Future

New Zealand's transport system is built around private cars as the default. Could car sharing be a keystone to accelerate the transition to a more sustainable alternative?

timer

New Zealand’s passenger transport system is in a bad place. Outside of a few small European nations with less than 10% of our population, we have the highest rate of private vehicle ownership in the world: 897 vehicles per 1000 people. Around 80% of commuting trips in New Zealand are made in a private car - dwarfing the use of public transport (6.5%) and active transport (walking/cycling, 11.3% combined).

Our trends on vehicle size and emissions are also moving in the wrong direction: in 2018 utes outsold electric vehicles in New Zealand at a rate of 64 to 1. Emissions from transportation almost doubled between 1990 and 2018 - contributing to the increasing impacts of the climate crisis and a continued increase in extreme weather events.

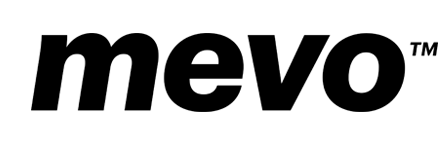

The Cycle of Car Dependency

Unfortunately, electric cars aren’t going to be a silver bullet for the problems in our transport system. While they do produce zero tailpipe emissions - and radically fewer emissions overall (60% less including built emissions and those from electricity generation) - they don’t solve any of the other problems we have as a result of cars being the dominant way we get around. Replacing the 4.5 million cars in New Zealand with 4.5 million new electric cars doesn’t fix our transport system.

As well as the direct emission impacts of private car travel, we’re beginning to understand the wider impacts of so many cars everywhere. This ranges from the micro-particulates generated when tires are worn down on the road, to the 300+ annual deaths in car accidents, to the impacts of the private car’s dominance on how we build housing, roads, communities, and cities. Congestion in Auckland alone is estimated to cost around $2B per year to the local economy.

The prevalence of cars leads to many knock-on decisions - both individual and systemic - around how we plan, consent, and build our towns and cities. If the assumption is that everyone owns a car, then homes need to be built with spaces for those cars. This means they’ll tend toward being larger houses on larger sections, which means they’ll be further from where the people living in them work or shop. Those people will need to use their cars to get around since these subdivisions aren’t usually planned with transit included.

Because the marginal cost of using your car is low once you own it, living further away and driving everywhere doesn’t seem like a problem - until everyone does it. A recent housing development just outside of my hometown, Nelson, is tipped to double the amount of car traffic on nearby roads, while only providing around 70 new homes. We’ve been trying to build our way out of this problem for decades; wider and bigger roads have only led to more congestion. This phenomenon is actually known as the Cycle of Car Dependency - you can read more about it on Wikipedia.

Another huge impact of the prevalence of private cars is our perception and treatment of alternatives: public transport, bike lanes, and pedestrian infrastructure. Why would you take the bus if it’s crowded, infrequent, or doesn’t stop nearby, especially if you already own a car? Cycling can be truly deadly on roads without designated, separated space for bikes. Conversely, our high rates of private car ownership make the case for investing in these alternatives tricky; cycleways and bus lanes are regularly opposed loudly by those who feel entitled to the car parking or vehicle lanes they replace.

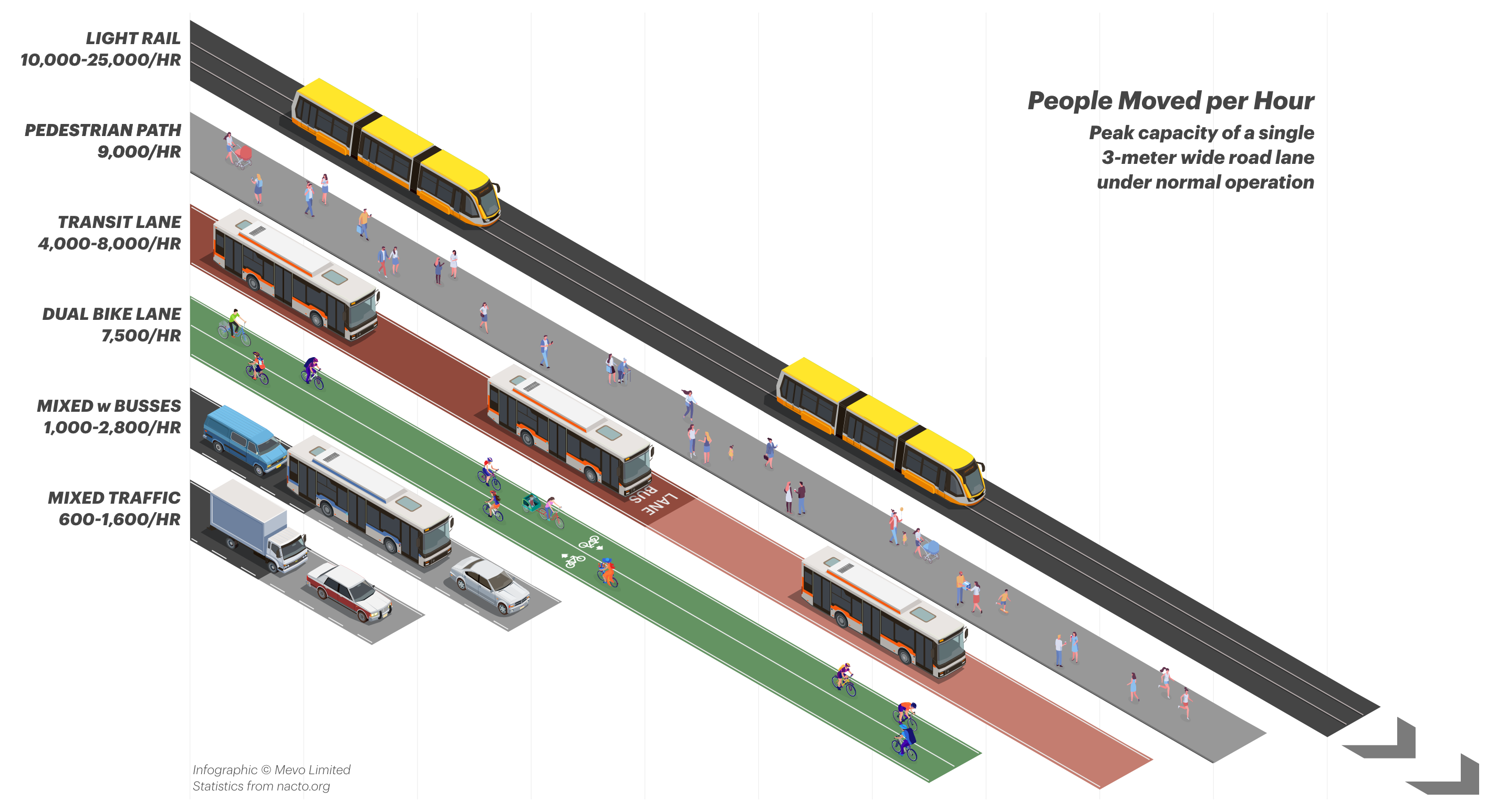

This is despite the fact that vehicle lanes are, by far, the least efficient way to move people - for the space they take up. A standard three-metre wide lane moves between 600 and 1,600 people per hour in private cars depending on the flow of traffic. That same width of road space can move 7,500 people as a two-way bike lane, or up to 8,000 people as a bus lane. Lanes used for car parking move precisely zero people, and yet ubiquitous on-street parking is an almost universal expectation in New Zealand.

For all of these reasons, autonomous cars also won’t be a silver bullet - the fundamental size and capacity of a car is part of the issue. Autonomous cars - when they eventually arrive - will get stuck in traffic with human-driven cars, goods vehicles, and the rest of it. Fully autonomous driving can be much better applied to buses of various sizes - allowing more high-efficiency routes to be established with fewer drivers required. It’s also going to be far easier to electrify our national bus fleet than it will be to do the same for our cars.

The Ownership Problem

We’ve mentioned several of the issues caused by widespread car ownership already - but potentially the largest one is how poorly private cars are utilised. The average car is parked 96% of the time - a utilisation rate of just 4%. Typically, it’s the second-largest purchase people make after their home.

If you live in a town or city and look up and down the streets you live and work on, you’ll see thousands of cars parked all around you, all the time. There are entire buildings in our cities just to park our cars while we’re not using them. There’s no other class of tool or asset that’s so widespread, costs so much, and takes up so much space - that we get so little use out of.

So, is the solution to ban all New Zealand’s cars, then? Build out passenger rail, bus services, and bike lanes in every town and city? Perhaps if you could wave a magic wand this could work; but unfortunately the real world is a little more concrete. Investments in the infrastructure for alternative transport options like this take many years, and need to be paired with the right housing and urban development to go along with it. The reality is that we’ve been building our current car-centric system for decades; as we’ve previously discussed on this blog, Auckland had a large electric tram network up until the 50s.

In fact, we’ve become so entrenched in our car centric world that it’s difficult to imagine doing some things without getting there by car. Many places you might sometimes want to go - regional towns, shopping malls, activities, national parks - don’t have any alternatives for getting there. Your Driver’s Licence is even the de-facto form of personal identification - New Zealand doesn’t have another state ID as many European countries do. There are plenty of journeys where the upsides of using a private car become apparent; the convenience, flexibility, and privacy are all hard to match with other ways of getting around.

Forgoing cars just isn’t an option for many people today based on where they work and live. Many people, however, do have options - but need a car sometimes, for those trips without great alternatives. So, they need to own one. Families need to own a second or third car for the peak times when they need more than one at once.

The problem isn’t the cars themselves - it’s the business model:

car ownership as the only option.

Until recently, because there was no easy way to access a car without owning it, to get any of the benefits of car access you had to buy all of the car. Many of the costs of owning that car disappear into your weekly/monthly budgets: depreciation, insurance, storage, WOFs etc. The marginal cost of each trip then feels low to you - maybe it’s a few dollars for fuel and another few for parking. You’re less likely to use a bike, bus, or train to commute - unless there are serious dis-incentives to driving - because the cost of those trips (money/effort) feels high compared to taking your car. You’re also responsible for storing it for 96% of its life, which influences your decisions around where you live and where you travel to.

How Car Sharing Unlocks the System

Car sharing isn’t a new idea; it’s been operating in various forms in parts of the world for over 30 years. Allowing access to a car without owning it is the common goal for all car sharing operations. Advances in smartphone technology have allowed services like Mevo to develop this concept - pushing the envelope of convenience and flexibility.

If you can quickly and easily access a car that isn’t yours - owning one can look much less appealing. When there is something to compare it to, the hidden ongoing costs of owning a car can be thrown into stark relief. The cost of using a car sharing service for those occasional use-cases is often far, far lower than the costs of car ownership - and you’ll end up driving a newer, cleaner, safer car as a bonus.

Without car sharing to bridge the gap for those car-critical trips, this comparison doesn’t often happen - and people don’t think twice about the car they own. Even if they do, the lack of an alternative for when they actually need a car makes considering other options difficult. We’ve learned from our members that those who give up owning a car transition to more of a menu-based approach to their transport; picking and choosing modes based on what’s nearby, available, and cost-effective for each trip they take.

Numerous studies on car sharing operations have shown that those who use them own fewer cars, and increase their use of public and active transport, which as we discussed earlier are much more efficient on space and the environment. In Wellington, studies have shown that 11 private cars are removed for each car share vehicle. In North America, studies have found between 9 and 13 vehicles are replaced by each shared car, while the limits referenced in another study are as wide as 5 to 23 vehicles replaced - depending on location and methodology used.

The secret to achieving this is that Mevo vehicles are much, much more utilised than the average car - spending less time in parking spaces and more time moving between locations whilst being rented. During busy periods we regularly observe around 40% utilisation of our vehicles across a 24 hour period - around 10x the comparable for a private car.

Unfortunately, whilst other services such as micro mobility (e-scooters) and ride hailing (Uber, Lyft, Ola) expand the “transport menu” for those who are browsing, their introduction isn’t always associated with a decrease in private vehicle ownership among users. Some evidence suggests that Uber and Lyft drive a slight increase in vehicle ownership, due to drivers buying new vehicles to drive for these services. Unfortunately, there aren’t many other great options that replace the utility of a car that you own.

Car sharing services also benefit those who never use them. Your neighbours who pick up these services and sell their infrequently used cars are going to free up parking and road space in your neighbourhood. This point is worth labouring: if you need to own your car, car sharing and complementary investments in biking and public transport infrastructure are going to make it easier for you to drive your car over time. This might not happen overnight, but it’s the only path to reduce congestion and competition for parking spaces.

A Transport System Keystone

In a lot of ways, our transport system in New Zealand today looks a bit like a monoculture. We have a system that favours a single mode of transport and produces a lot of negative externalities. What we need to move towards is an ecosystem, where different types of transport coexist together, and provide mutual support and benefits.

There are many examples in nature of what’s called a keystone species. This is analogous to the role of a keystone in an arch - holding the system up and in balance. They have a disproportionately large effect on their ecosystems relative to their numbers, and influence the distribution of other organisms. Without them, their ecosystems can become unstable and favour a smaller range of species, or even a single one.

Sea otters are a good example: they prefer coastal marine habitats dominated by kelp stands. These plants, various species of algae, can reach 40 metres from the sea bottom to the surface. Various species of sea urchin feed on this kelp, and the otters in turn feed on the urchins.

In this way, the presence of the otters helps to protect the underwater kelp forests from the sea urchins. When the sea otters of the North American west coast were hunted commercially for their fur, their numbers fell to such low levels that they were unable to control the sea urchin population. The urchins then grazed the kelp so heavily that the kelp forests largely disappeared, along with all the species that depended on them: countless fish, shellfish, and marine birds and mammals. The good news in recent years is that reintroducing the sea otters has led to a reduction in urchin numbers, enabling the kelp ecosystem to recover - along with the ecosystem that it supports.

In the transport ecosystem of the future, you can think of car sharing as a keystone species. By giving people access to a private car, without feeding the cycle of car dependency, car sharing encourages people to take a multi-modal approach to how they get around - especially when they can’t rely on public transport for 100% of their trips. This allows for other transport “species” - public transport, walking, cycling, micro-mobility, and ride-hailing - to flourish and find their natural equilibriums.

Growing & expanding car sharing complements work that takes longer to implement; transit oriented development, densifying our towns and cities, and building or converting transport infrastructure that isn’t just for cars. Continuing to electrify all of our transport system must also continue at pace if we’re to stand a chance at preserving our way of life in the face of climate change.

Join us in The Future

On this blog, we’ve started telling just a few of the stories of people who are finding ways to change how they move around. Perhaps you’ve found some food for thought, or a new perspective on just how heavily our transport system favours car ownership.

To summarise: even if you’re the most die-hard fan of your car and driving it, a varied, multi-modal transport ecosystem will benefit you. More options for other people will help them choose the most efficient ones - leaving more road space for the remaining cars. And car sharing can be the keystone that holds the system in balance, and gives people true choice in how they get around.